How Much Do Biological Ties Really Matter?

Sperm and egg donation never promises a relationship. It’s true

Being lesbionics in rural Nova Scotia meant our birth plan had an extra bit that I knew I didn’t want to potentially negotiate after pushing something the size of a small watermelon out of my nether regions. Registering our son’s birth.

When Lisa and I wanted to get married in the UK we couldn’t and settled for a civil partnership and then marriage in Canada. Why? Solicitors told us they weren’t certain our ceremony in the UK would be recognized and provide the parental legal rights for the child we were envisioning.

An excuse for a new dress and party. I was in.

When pregnant I began to worry again and met with several solicitors that advised family law had not yet caught up to same sex families. Lisa might need to adopt our son and we were advised to get her name on his birth certificate. Something we had not considered.

It was an awkward conversation with the rural hospital we had planned our birth with.

“Hi um we are giving birth in your hospital and are a same sex family. I know, why do you need to know that? You see we plan on putting our names on our son’s birth certificate and need to check you are going to be okay. What’s your name just in case on the day we run into a homophobe? ”

While there were plenty of birthing moments where our planning was laughable, the birth certificate signing was smooth.

I have been thinking about our experience as same sex parents and weighing my feminist principals, listening to same sex couples discussing surrogacy in the UK and their legal parental hurdles.

The surrogate is the legal mother of the surrogate child from birth until legal parenthood is transferred to the intended parents through a parental order made by a family court. This remains the case even if the child is not biologically hers. If the surrogate is married or in a relationship, her partner will also assume legal parenthood status of the child from birth until the parental order is made.

You can start the process to obtain a parental order from 6 weeks until 6 months after the birth if certain criteria have been met, including the child being in their care, having the consent of the surrogate and at least one intended parent, being genetically related to the child.

While the parental order process is normally straightforward and it is usual for a child to be cared for by the intended parents from birth (with the surrogate’s consent). A portion of this I would imagine is a terrifying way to begin to be a parent at the same time as you are just well trying to be a parent which is terrifying.

If the conception in a surrogacy arrangement takes place in a licenced clinic and the appropriate consent forms are completed, if the surrogate is not married, the intended parent who provides the sperm can be registered as the legal father on the birth certificate.

A parental order though would still be necessary to transfer the legal parenthood of the second parent. Making those with no genetic claim in a more precarious position.

All this while also considering the surrogate who entered an agreement albeit not legally binding, before the birth. They may though have not fully prepared themselves for what is unknowable, the potentially emotional process of giving life to another human.

I don’t have a neat way of wrapping up a conclusion. Only the messy experience of being a human, mother, female. With part of my identity that includes a growing group of differently constructed families who are having to consider ethical and moral possibilities in creating people.

Perhaps the consideration and pondering in itself is no bad thing.

What I am clear about though is the right for every one of those children to know their beginnings.

Sperm and egg donation never promises a relationship. It’s true

The above is from an excerpt of her book, I

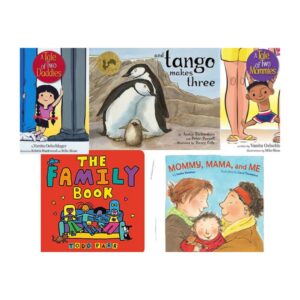

The stories we are told as children play a role in who we become when we grow up. After all we eventually narrate our own lives. The character who inhabits books and screens have an impact on how children see themselves and others. Representation is so important.